Monks, Mummified

Part I of II

The Capuchins were not ones to shy away from discomfort.

Physically, mentally, and socially, these religious devotes settled into and made an art of discomfort, in life and in death.

Where did the Capuchins get the idea that less is more?

The late Pope Frances chose his name as a nod to St. Frances of Assisi, father of the order of the Franciscans. Founded in 1209, the Franciscans inhabited a life of poverty, simplicity, and service. They traveled their native Italy as beggars, preaching and subsisting off the generosity of others, while claiming no earthly materials as their own.

Over the next several years, the extreme poverty required of Franciscan friars was lifted, allowing members to embody lives of simplicity and material detachment without the element of essential destitution. This remained a polarizing issue within the church, leading to the formation of several breakoff orders.

In 1525, Matteo da Bascio founded one such subsidiary; the Order of the Friar Minor Capuchins. Matteo believed the Franciscans had strayed too far from the values of St. Frances of Assisi, and he wanted his new order to reflect the pious asceticism St. Frances was known for.

The Capuchins lived in small communities of eight to 12 members. Their houses were sparsely furnished and stocked with limited rations. The little the Capuchins did have, they were required to beg for, as their vows forbade them from touching money. As for dress, they went barefoot, donning brown tunics with large, pointed hoods (cappucio in Italian), and a woolen rope for a belt.1

Capuchins reside in and serve the most impoverished communities in their cities, continuing to value an austere lifestyle committed to prayer, charity, and fraternity.

Fun fact: the cappuccino is named after the brown hue of Capuchin garb!

If you take a trip to Spain and visit The Girona History Museum, you will find the cemetery of the Capuchin monastery, Saint Anthony of Padua. Built in 1753, this cemetery included a desiccator on the ground floor, which served as a chamber to facilitate mummification of friars’ bodies.

After death, the body was seated upright upon a perforated bench in one of 18 alcoves. The low-humidity chamber would allow the corpse to dry out, while preserving the body. Two years later, the body would be removed from the desiccator, dressed in traditional religious attire, and placed in a nearby room. Here, the mummy served as a memento mori for the community; a reflection on the brevity of life and the certainty of death.2

Bare-bones lifestyle carries into death.

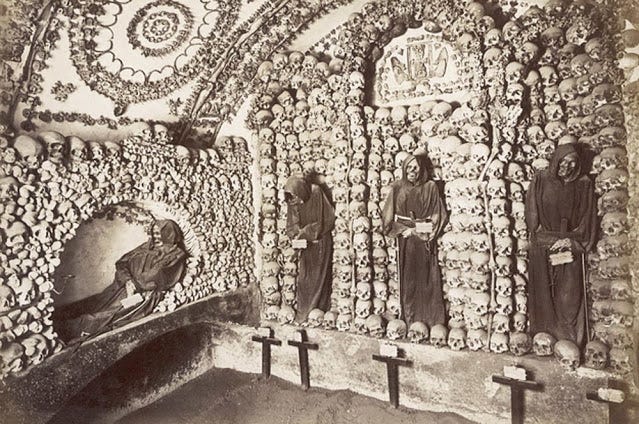

Across the Mediterranean Sea in Rome lies the Capuchin Crypt; an ossuary housing the skeletal remains of 4,000 Capuchin friars. The bones line the walls of the crypt in grand designs, creating a cathedral-like atmosphere for the friars’ nightly meditation and prayers.

The Capuchins believed in stripping things down to the bare essentials when it came to their existence. They also valued the most basic version of our earthly selves after death; our skeletons. But why?

While viewing the body of a loved one at a funeral or wake before interment serves to actualize the reality of their death, preserving the whole body, as in mummification, or the bones for viewing long after death serves to actualize the reality of our eventual death.

The Capuchin’s practice humility in their lifestyle and preach humility in their ways. One way of keeping themselves humble was remembering that they are but fragile beings, always one step away from being stripped of this life.

Inscripted in the Capuchin crypt is the reminder,3

What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you shall be.

Thank you to

of Sparks of Light for sharing her photos and inspiration for this post. More to come from Trudi in Part II!

Laura this is fascinating and reveals so much more than I learned at the museum. And the cappuccino fact! I’ll not look at them in the same way! Thank you for this and for bringing my pictures to life! ✨