“I give this film a three tissue rating,” Dr. Martin forewarned as he switched off the classroom lights. We all knew what that meant, but we weren’t scared. We were thanatologists.

During my years of studying death in the basement of Rosenstock Hall at Hood College, I shed many tears. Those tissue ratings of Dr. Martin’s were no joke. We shared heartbreaking stories, watched heartbreaking stories, and examined death, dying, grief and loss from every angle imaginable. Yet somehow, we always walked out the door, back up the stairs and into the sunlight, in one piece.

Our thanatology program was not therapy, this was made clear from day one. We were academics, and it was accepted that we would cry as we learned. In fact, it’s possible that our tears made our learning possible.

Our eyes produce three types of tears, each with a different chemical makeup:

Basal tears: Keep eyes lubricated throughout the day.

Reflex tears: Protect our eyes from irritants, such as smoke.

Emotional tears: Produce in response to sadness, happiness, fear, etc.

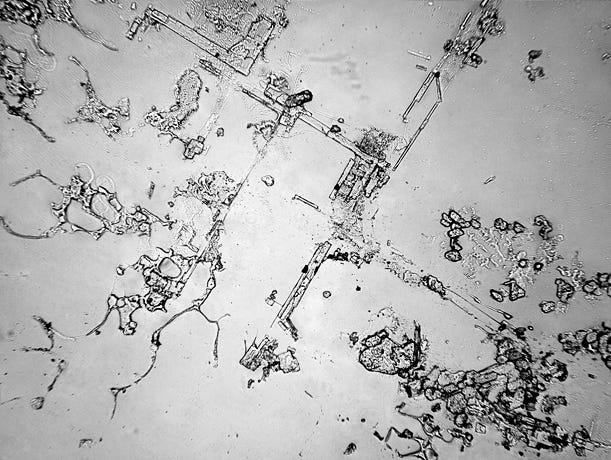

Each type of tear has it’s own composition in addition to a unique purpose, which is part of what makes the tear of grief above look different under a microscope than, say, a basal tear released in an arid office space.

Emotional tears contain high levels of stress hormones and other toxins in comparison to basal and reflex tears, meaning that when you have “a good cry,” you’re physically flushing stress out of your body. Additionally, the neurotransmitter leucine enkephalin is released with the flow of emotional tears, acting as a natural painkiller.

Crying activates the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS), responsible for our “rest and digest” response, in tandem with the sympathetic nervous system’s (SNS) “fight, flight or freeze” response. Thanks to this PSNS activation, our heart rate slows, respirations decrease, blood pressure stabilizes, and we’re gently lowered to a state of calm as we cry it out.

What else does a cathartic crying session do for you? It releases into your system:

Oxytocin: A hormone promoting feelings of bonding and well being.

Endorphins: Which improve mood and reduce pain,

and

Prolactin: A key player in emotional regulation and stress reduction.

While most animals have tear ducts for producing basal and reflex tears - reflex and emotional tears are dispensed from the lacrimal gland, in the upper perimeter of the eye socket - humans are the only animals who produce emotional tears. But why?

The most popular theory is that emotional tears are a social cue; a silent distress call invoking support from the community. Seeing another person cry triggers an empathetic response in others, as we are hard-wired to offer aid at the sight of emotional tears.

Think about when you see a person crying in public: As you spot tears coming down the cheek of a downturned face, your attention is redirected towards them, perhaps you feel a constriction in your chest, thinking this person and possibly yourself are faced with a threat. Your heart rate increases as your sympathetic nervous system kicks in, and as you continue to assess the situation…you realize this person is looking down at their phone, laughing hysterically at a video.

They were crying happy tears, but it still got your attention, and in today’s social climate, we love to be noticed. Maybe they don’t need to be sincerely happy tears or sad tears to get us the likes we crave.

, sociologist and author of the Substack, The Sociology of…Everything, gives us these questions to ponder about the performative aspects of tears:We love to reward actors for their ability to cry on-demand and we celebrate their ability to seemingly access such raw emotion (nevermind that those tears are often assisted by a tear stick - menthol-infused wax that generates tears). Is crying an accomplishment? I don't know. A modern twist on this which fascinates me is the trend of filming yourself while crying and posting it to social media - perhaps to speak out about an issue or show how devastated you are by something. If we break down the mechanics of that, wouldn't the act of taking out our phones and filming ourselves remove us from that genuine state of feeling? It flips us out of our emotional state and into a logical, strategic mode, which usually stops the tears, rather than encouraging them. And what is the purpose of wanting to be witnessed in that state of crying? Are tears meant for private moments spent alone, with those we trust and love? Or have we decided as a society that there is value in broadcasting our tears? What is the social value gained there? Is it a "cry" for empathy? Or a demonstration of an Oscar-winning performance?

As Anna points out, tears are awarded in contexts in which they’re a few degrees removed from genuine emotion. But when they are a genuine emotional reflex, they feel vulnerable. You’re telling someone you’re emotionally distraught, or blissfully happy, as it may be, giving them a glimpse into your inner world. Whether you want to or not. And sometimes you don’t want to.

Not everyone loves a good cry. If you’re trying to suppress an undercurrent of sobs, that doesn’t feel good. If you’re uncomfortable or ashamed to cry in front of others, or even by yourself, that also does not feel good. An individual’s personality, culture, and upbringing play an important role in shaping how they feel about tears, and how tears feel to them.

Many cultures view crying as a sign of weakness; a mental and emotional breakdown when things get too tough. But as we’ve learned, crying is the body’s mechanism for coping with and processing difficult situations and feelings. When you allow yourself to cry, you’re utilizing an evolutionary tool. But if you’re taught from a young age to put on a brave face and persevere, you may not know how to use that tool.

In Japan, Hidefumi Yoshida has devoted his career to teaching his fellow Japanese how to cry. His service is called Rui-Katsu, meaning, to seek tears. Yoshida refers to his job as a tear teacher, and he helps people access their internalized, suppressed emotions so they may experience the mental and physical benefits of emotional tears.

But the work of the tear teacher doesn’t end after class. Over the years he has established crying clubs, where people gather in public to watch emotionally evocative videos, crying tours, and crying cafes. He feels so strongly about the physical and mental benefits of crying, that he’s all but turned it into a public service.

As humans, we’ve taken control of our emotional tears. We have bottled them up, sold them for profit, weaponized them, and ostracized them. But the grief therapist in me is suggesting you give tears a chance. You don’t need to take a course in crying, but the next time you start to well up, whether it be over the death of a dear friend or Sarah McLachlan’s SPCA commercial (it’ll get you!), remember that tears are a service your body is doing for you, relieving stress and supplying comfort.

Laura this is fascinating. I do bottle up my tears but reading this, I think I need to learn how to release them. Thank you. ✨